Goodbye to Lori Lightfoot, The First Transplant Mayor of Chicago

Lightfoot tried to run Chicago as an 'outsider': using new media tactics without an old-school power bloc. This was a bad idea.

Lori Lightfoot is from Chicago.

This is a strange way to start a goodbye to the current mayor of Chicago.

Lightfoot’s loss last night in the general election leaves Brandon Johnson and Paul Vallas to duke it out for mayor in a runoff vote.

Her loss is no surprise — Lightfoot’s 2023 campaign has been as chaotic as the four years she’s spent as mayor.

Lightfoot was an unusually flamboyant mayor in a city known for flamboyant mayors.

To start by saying Lightfoot is from Ohio is to start with what is probably the least interesting fact about her.

Who cares where this Mayor — who cussed out aldermen on a monthly basis, who brought her armed security to buy Modelos, whose dick is bigger than all the Italians’ — grew up?

Or, if you’re going to get into identity at all, why talk about Ohio when you could talk about the firsts Lightfoot would prefer to mention: Chicago’s first Black lesbian Chicago Mayor?

It matters that Lightfoot is from Ohio because Lightfoot’s transplant status shaped every facet of her term as Mayor, from her emphasis on national media attention to her consistent stalemate with groups on both the left and the right.

Lori Lightfoot was Chicago’s first transplant mayor, prioritizing new media over old-school power blocs: which is why her four years in office were so fraught.

These tactics weren’t strong enough to build anything that could beat the broken fragments of Chicago’s old power blocs (at least, when it came to getting anything done).

And as a result, Lightfoot ended up doing a lot of weird stuff.

So we say goodbye, let’s take a look at why Lightfoot’s transplant tactics made her 4 years in office so wild.

Quick Review: Lightfoot Wasn’t a Very Good Mayor

Smarter, more politically savvy people than I will have takes on Lightfoot’s policies, her failure to support Chicago’s Black and Brown communities, and her overall depressing legacy.

A political lightning rod for both the Right and the Left, as her term passed, Lightfoot increasingly found herself unable to count on solid support from any corner of the city.

To describe Lightfoot’s four years this way isn’t indicative of sympathy: part of what made Lightfoot’s tenure so infuriating was that she made innumerable bad choices that made her enemies everywhere — over and over again.

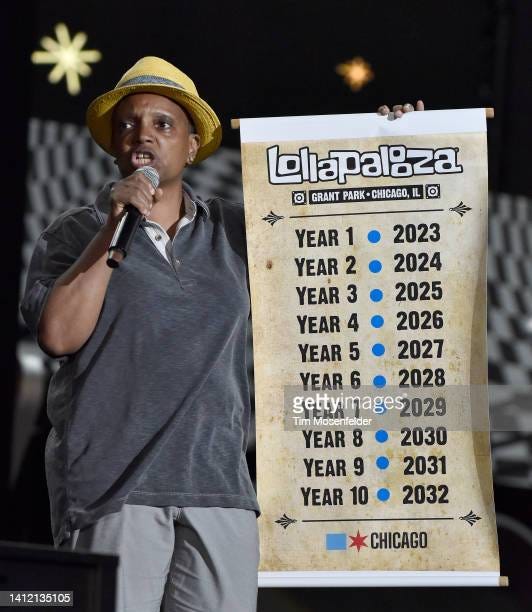

A quick highlight round of Lightfoot’s audacious and or morally suspect moves: comparing her dick size to the dick size of every Italian in the city (hers is bigger), a PR campaign for Chicagwa (canned Chicago water) in the midst of a scandal about lead in South and Southwest neighborhood water pipes, and uh, whatever was happening in this Lollapalooza ad.

I wrote some other reasons down a year or two ago. The list has only gotten longer.

On a regular basis, Lightfoot did the kind of things one environmental organizer described as “bad choices made worse because they didn’t make any sense.”

But Lightfoot’s choices, however nonsensical, were tied to a larger strategy, however flawed. They were based on tactics she used from the very beginning, in the initial stages of her Mayoral campaign.

The Bad You Don’t Know v. The Bad You Know

The runoff of the 2019 Mayoral Election felt like it lasted longer than the general election — but that’s probably more about my state of mind at the time than the campaign itself.

After a chaotic 6 months, the 19 candidates of the general election were narrowed down to 2, both of whom were Black women: Lori Lightfoot v. Toni Preckwinkle.

Toni Preckwinkle, a former teacher and President of the Cook County Board of Commissioners, was an old-school Chicago candidate.

As a consequence, her election campaign did old-school Chicago candidate shit.

Preckwinkle’s only campaign video featured Jan Schakowsky (no one knows who that is). In the video, the two of them converse almost inaudibly about being a woman in politics at Piccolo Sogno, a dimly lit restaurant near Chicago City Council (no one knows where that is).

In the lead-up to the Chicago 2019 election, Preckwinkle was endorsed by the Chicago Teacher’s Union and many other people I had never heard of, the type of person that made old organizers who wanted to repost Instagram Stories on Facebook nod approvingly. (They all loved that video, btw.)

Another problem with old-school Chicago shit: it comes with old-school Chicago baggage. And Preckwinkle, whose political tenure had begun 30 years before, had plenty of old-school baggage.

“Why don’t you like Preckwinkle?” I asked one of the guys I was working on Wilson Men’s Hotel with on the steps next to the place where they do press conferences in City Hal. We had an hour to kill before anyone else would get there. He shook his head forebodingly.

“Toni’s bad news: she has been since the 90s.” He said. He told me about Preckwinkle’s role in the soda tax, her disrespect for the South Side as she climbed the ranks as alderwoman of the 4th Ward, and a rude thing she had said to his uncle in 1994.

Like most Chicago politicos, his analysis was a blend of meticulous policy and neighborhood gossip.

“We know what Preckwinkle will be like,” he said. “At least with Lori, we don’t know what we’ll get.”

“And that’s a good thing?” I asked.

He shrugged. “That’s as close to a good thing as you get in Chicago.”

Letting in the Light

Lightfoot seemed to count on this kind of non-ringing endorsement.

“Let the Light In,” her 2019 campaign slogan, was about challenging the establishment politics that kept Chicago in the dark. The hope seemed to be that voters would pick her, who they didn’t know, over Preckwinkle, who they knew and didn’t like. This was her transplant tactics at work, in the fabric of her campaign: I don’t know you, so maybe it will be fine.

Lightfoot’s campaign, much lauded for crossing the racial lines of Chicago machine politics, appealed to white, Black and Latinx voters, carrying all 50 wards — but there was never a distinct group in particular who backed her campaign.

Most of her endorsements came from local affiliates of national identity-based organizations (The Victory Fund, LPAC, Planned Parenthood), the Democratic establishment, and aggressively pragmatic local unions (Unite Here Local 1).

Compared to Preckwinkle, Lightfoot’s campaign used digital media in a surprisingly sophisticated way for Chicago politics, appealing to young progressive voters with targeted, well-designed media from memes to television appearances.

Though Lightfoot swept the election in every single ward, she also appealed in particular to a certain type of voter — one appalled enough by President Trump, still in office in 2019, to be galvanized into national action, if not necessarily local awareness.

In a city known for organizing through strong neighborhood blocs, Lori won her election through media and digital strategy, Democratic funding, and quite simply, being “not the other guy.”

Beyond her time as a prosecutor, running Chicago’s Police Accountability Board, there was little out there (that wasn’t created by her campaign) to help the discerning voter get a sense of Lightfoot’s policy ideas.

A few prescient leftists (also Chance the Rapper) cautioned against choosing Lighfoot in the runoff, but their warnings were abstract, easy to dismiss as ideology — “never trust a prosecutor” said one. Others brought up Lightfoot’s pettiness in assorted court appearances, her personal fervor in indicting Black Lives Matter protestors, her disregard for the youth movement working to stop the building of a 35 million-dollar police academy. But for those not following these conversations, and even to those that were — it seemed there were no major, seismic reasons to vote against Lightfoot.

So, with liberal rhetoric that sounded good enough and an emphasis on identity, many well-meaning progressives, both from Chicago and not, voted to Let the Light In.

“We are each other’s business; we are each other’s magnitude and bond,” Lori said in her acceptance speech, quoting Gwendolyn Brooks. “Our challenges can only be solved if we face them together.”

Lightfoot’s first win destabilized innumerable implicit understandings about how power works in Chicago – and how power will work in the future.

I listened to Lightfoot’s acceptance speech on the radio in an Uber from the South Side to the 46th Ward Race Election party, frantically refreshing the county election website. The 46th Ward Race Election party ended up being one of the least fun parties I had been to in a while (nothing like ballot count confusion to ruin a vibe), so I shouldn’t have rushed to get there. But at least I got to hear her speech.

And as Lori described her vision for Chicago, talking at length about her gratitude for her mother, Anne Lightfoot, still living in Ohio — I thought “Damn. Not bad.”

“I voted for her,” the Uber driver said, an older man from Bronzeville. “I saw her ads, and think she’s going to change the city.”

“Huh,” I said, interested. “Maybe Lightfoot as Mayor will actually be okay?”

Of course, she wasn’t.

What Makes for a Good Mayor?

Let’s not pretend that Lightfoot ever had an easy task ahead of her as Chicago’s Mayor.

There is no such thing as a popular Mayor in a global unprecedented pandemic.

There is no such thing as a popular Mayor who starts her term with a gigantic fiscal cliff, an already hostile police force, and a limited power bloc, nor one that wants to end corruption in Chicago, where, you know — there’s a lot of corruption.

In retrospect, Lightfoot, for all her digital savvy, had few models for what it would like to be a “Good Mayor,” especially as an outsider candidate without a power bloc.

Even Harold Washington, Chicago’s first Black Mayor and first organizing Mayor, who was able to strongarm even “people who really hated each other” into a coalition strong enough to beat Jane Bryne (not saying much, but it was still an impressive coalition) died in his first term. His power in office was stymied by the Council Wars before we could really see what a “Good Mayor” of Chicago might look like in action.

Say what you will about Daley and Rahm — it’s debatable whether Chicagoans outside of Bridgeport or the Loop would describe them as ‘good mayors,’ but they definitely demonstrate that corruption and choosing business over everything sure can get things done. (“The streets are cleaned. The garbage is hauled. The snow gets plowed. The street lights work. The trains run on time.”)

If she’d been elected, Preckwinkle might have been in the same position as Lightfoot at the start (though her endorsement by the Chicago Teacher’s Union probably would have helped her at least avoid an embarrassing resolution to the 2019 strike).

For all of the problems with Preckwinkle’s smoky inaudible campaign videos, they showed she understood City Hall.

Lightfoot, in spite of her high-production quality videos and national media appearances, couldn’t say the same.

Transplant Tactics in Office

Without a power bloc or any of the tools her predecessors had used to manage City Council, Lightfoot leaned on the tactics and strategy that got her in office: the power of the media.

During her first few months in office, her media appearances remained prolific — though in national news, not Chicago outlets. She was everywhere — and sometimes even funny on social media (at least by politician standards). And Lightfoot’s first few acts as Mayor, like making Chicago a sanctuary city, attracted national attention — though they didn’t necessarily lead to material change for undocumented people in the city. Lightfoot’s 2019 campaign communications strategy was run by Joanna Klonsky, a hometown Chicagoan tied deeply to Chicago’s transplant new media world. Though she later left the administration, Klonsky was (presumably) responsible for many of Lori’s initial media wins— including her much meme-ed presence reminding everyone to stay home once the pandemic hit. No one had brought this kind of branding and media savvy to the Chicago Mayor’s office before (no offense to Rahm Emanuel’s podcast, with 2 listeners) — at first, it worked really well.

But ultimately, Lori’s transplant tactics backfired — and when they did, they really backfired.

Men’s Warehouse Icon

Early on in her term, there were certainly signs that Lightfoot might not have everything under control.

Police accountability measures stalled a lot for a mayor who ran as a police reformer.

But greater attention to Lightfoot’s missteps on a national scale, really began with her handling of the protest at the Christopher Columbus statue in Millenium Park — when she called in CPD groups that wildly escalated the situation, leading to significant injury of young protestors.

Things continued with tension — until Lightfoot ignored tens of thousands of demonstrators who demanded she defund the CPD — a movement responding to the murder of George Floyd, that relied on the same online and national media mobilization that Lightfoot’s campaign had used in 2019 — that her transplant tactics started to fall apart.

Lightfoot’s frustrations mounted — whether the abundance of media about her blow-ups was because of Lightfoot’s exceptional temper or just her staff’s exceptional willingness to leak emails, they appeared in national media endlessly.

Then: a death knell.

The internet got involved — the very force that had meme-d her affectionately only a few months before.

From “Lori Lightfoot is a Cop” to TikTok impressions to scathing denunciations of her suit tailoring, Lightfoot’s sanitized and publically sanctioned content production was no match for the scathing power of the Queer internet.

It’s important to note that this national vitriol went far beyond the Left: Lightfoot’s policies and the wrath of the FOP drew Fox News and conservatives everywhere down upon her. Lightfoot was a lightning rod because of her identity and her policing policies, sure, but also because of her incredible ability to antagonize everyone all at once.

Between the Left and the Right, Lightfoot quickly became one of the most derided (and meme-d) officials in the country.

Lori’s outsider run was exceptional because she ran and won without a single established power base in the city.

But there was a limit to Lightfoot’s win — she may have reached hundreds of thousands of people in the election, but she couldn’t reach those same thousands of people for every ordinance, every council subcommittee meeting.

And in those moments, community groups, from the FOP to the CTU, could strike. Their small bases took Lightfoot down with a million cuts of action emails and procedural policy concerns.

Combined with decentralized movement moments that used national media and digital strategy similar to Lightfoot’s own, Lightfoot’s reformer outsider strategy was slowly but surely worn away with every press release.

For a more established Mayor with a power bloc, maybe none of it would’ve mattered. But with Lori, who lacked any sort of equivalent base and relied on national media, it was devastating.

As national attention around Lightfoot’s problems grew, her power to garner enough positive national media to keep the support of her progressive pseudo base was over.

Because she never had a power bloc inside City Hall to make policy moves — the outsider Mayor was stuck outside.

The Future of Chicago Politics— Transplant and Otherwise

As a Chicago transplant myself, I’m leery of implying that Lightfoot’s hometown matters much when it comes to her ability to govern.

Chicago’s power as a city is because of immigration, The Great Migration, and the millions of people who have made Chicago their home over the centuries. We’re all Chicago transplants, if you want to get technical (I guess except for the 65,000 Indigenous Chicagoans living across the city).

Lightfoot’s failings as Mayor come from her own focus on her outsider status. Her choices prioritized media over engaging with any other form of power — including the boldest (but most thankless) option: ignoring the broken power structures of the city and trying, however in earnest, to build new ones.

Identity category without grounding in place, politics, and context can be suspect when it comes to discerning motives in politics — that’s one big lesson from Lightfoot’s time in office. But there’s another lesson, more subtle but key to understanding Lightfoot’s terrible time in office.

Chicago’s weird messy neighborhood power structures, the remnants of both community organizing and a broken political machine, live on.

Lightfoot’s tenure, and the failure of her transplant-style politics, show that you still can’t ignore those structures, however, broken they might seem.

And whoever ends up as mayor (as well as the many new aldermen in this year's election) will have to find a better balance than Lightfoot did — no matter where they grew up.

👇 Want more exhaustingly comprehensive hot takes on niche issues in Chicago politics? 👇

Note: Toni Preckwinkle is technically a transplant too, from Minnesota. If you think this undermines the insider/outsider dynamics of the 2019 Mayoral race, fine — but if you express this to me via comment or tweet, I’m legally allowed to describe her campaign video to you at length, out loud. You’ve been warned.

Great read, H.